The first time I watched a customer interact with a conversational system and genuinely not realize they weren’t speaking with a human, I felt something shift in my understanding of what this technology could do. It was 2019, at a telecommunications company where I was consulting on their customer experience strategy. A caller had spent eleven minutes discussing a billing issue, cracking jokes, expressing frustration, and ultimately leaving satisfied with the resolution.

Afterward, reviewing the interaction logs, I noticed something the caller never had: they’d been speaking with an automated system for the first eight minutes before being seamlessly transferred to a human agent for the final resolution steps. The handoff was invisible. The caller’s satisfaction survey gave high marks across the entire experience, commenting specifically on the “agent’s” patience and understanding.

That interaction crystallized questions I’ve been exploring ever since: What makes conversation feel human? How close can technology get to genuine natural dialogue? And perhaps most importantly—what are the implications of systems that can convincingly simulate human communication?

After years of working with organizations implementing conversational systems, researching the underlying technology, and observing countless human-machine interactions, I’ve developed perspectives that go beyond the hype and the fear. The reality of human-like conversation generation is more nuanced, more impressive, and more limited than either enthusiasts or skeptics typically acknowledge.

What Actually Makes Conversation “Human”?

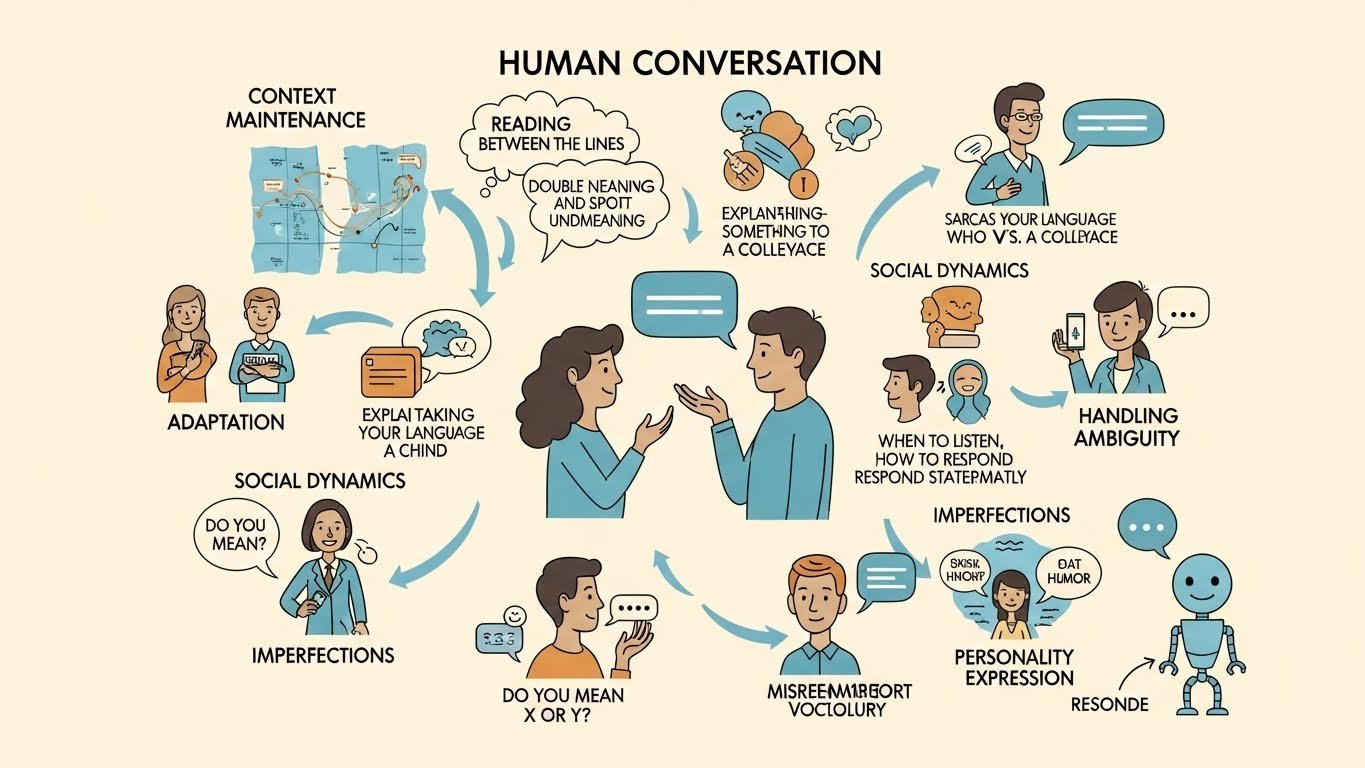

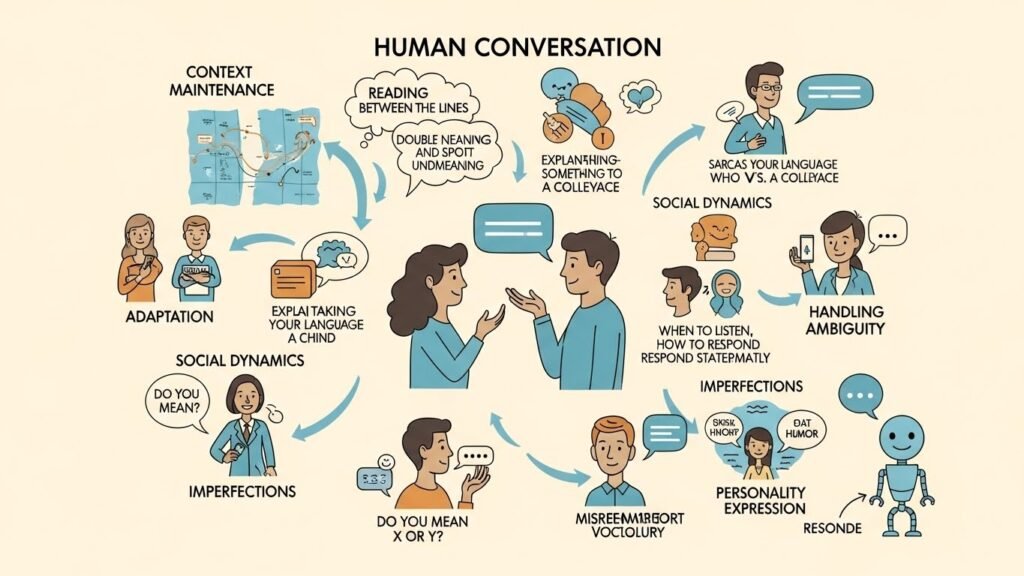

Before exploring how technology generates human-like responses, it’s worth examining what we actually mean by that phrase. Because when you start breaking down human conversation, you realize it’s remarkably complex.

Human dialogue isn’t just information exchange. When we talk, we’re doing dozens of things simultaneously:

We maintain context across long exchanges, remembering what was said ten turns ago and referencing it appropriately. We track who knows what, adjusting our explanations based on shared understanding.

We read between the lines, understanding implication, detecting sarcasm, recognizing when someone says “fine” but means something else entirely. We respond not just to words but to what those words signify.

We adapt our style based on who we’re talking with. The way you explain something to your grandmother differs from how you’d explain it to a colleague. We code-switch constantly and mostly unconsciously.

We manage social dynamics—taking turns, knowing when to interject, sensing when someone needs validation versus advice, recognizing when conversations are winding down.

We handle ambiguity gracefully. When someone says something unclear, we ask for clarification in ways that don’t make them feel stupid. We offer interpretations: “Do you mean X or Y?”

We make mistakes and recover. We misremember, contradict ourselves, and get sidetracked. Paradoxically, these “imperfections” are part of what makes conversation feel human.

We express personality through word choice, humor, emphasis, and the topics we gravitate toward. Conversations reveal who we are.

Generating responses that capture these qualities—or convincingly simulate them—requires technologies that go far beyond keyword matching or template responses. It requires something approaching genuine language understanding.

The Evolution: From Scripts to Understanding

Conversational technology has existed in primitive forms for decades. But what’s available today differs qualitatively from earlier approaches.

Early Chatbots: Pattern Matching

The original chatbots—ELIZA in the 1960s, ALICE in the 1990s—worked through pattern matching. They looked for keywords and responded with pre-written scripts. ELIZA famously simulated a psychotherapist by turning statements into questions: “I feel sad” became “Why do you feel sad?”

These systems could create momentary illusions of understanding but fell apart quickly under any sustained interaction. They had no actual comprehension—just clever deflection.

Rule-Based Systems: Controlled Responses

The next evolution brought more sophisticated rule systems. Customer service bots in the 2000s and 2010s could handle specific, bounded tasks reasonably well. If you wanted to check an order status or reset a password, carefully designed decision trees could guide you through.

But these systems were brittle. Anything outside the anticipated paths caused failure. They couldn’t handle the natural variation in how people express themselves. Every possible way someone might phrase a request had to be anticipated and programmed—an impossible task for open-ended conversation.

Machine Learning: Learning Patterns

Statistical approaches allowed systems to learn from data rather than requiring explicit programming of every response. These systems could generalize from examples, handling variations they’d never specifically encountered.

This worked better but still operated primarily at the surface level—patterns in word sequences rather than genuine meaning. They could sound more natural but still lacked understanding.

Large Language Models: Emergent Capabilities

The current generation of conversational technology represents something qualitatively different. Large language models trained on vast amounts of text have developed capabilities that weren’t explicitly programmed—they emerged from the scale and nature of the training.

These systems don’t just match patterns; they develop something resembling understanding of language structure, world knowledge, reasoning, and conversational dynamics. They can engage with novel topics, maintain coherent discussions over many turns, and generate responses that are remarkably context-appropriate.

The improvement isn’t incremental. It’s a step function. Systems that struggled with basic tasks five years ago now engage in sophisticated, extended dialogues that consistently surprise even researchers who build them.

How Modern Conversational Systems Work

Without getting too technical, understanding the basic mechanics helps set realistic expectations about capabilities and limitations.

Language Understanding

Modern systems process language through neural networks—mathematical structures loosely inspired by biological brains. These networks learn representations of language that capture meaning, not just word sequences.

When you type or speak to a conversational system, your input is converted into mathematical representations that encode semantic meaning. “I’m looking for Italian restaurants nearby” and “Can you find me some local Italian places to eat?” map to similar internal representations despite using different words.

This representation captures nuances humans might miss: the request is for restaurants (not takeout), Italian specifically, and location matters. The system understands the intent even though none of those constraints were explicitly stated.

Context Maintenance

Effective conversation requires memory. Modern systems maintain conversation history, using attention mechanisms to determine which parts of the conversation are relevant to the current exchange.

This is why you can say “What about French ones instead?” and the system understands you’re still talking about restaurants and want a different cuisine. The context persists.

The context window—how much conversation the system can actively consider—has grown substantially. Current systems can maintain coherent context across thousands of words, enabling extended dialogues without losing the thread.

Response Generation

Generating responses involves predicting what words would appropriately continue the conversation given everything that’s come before. The system considers the entire context—your message, the conversation history, and learned patterns about how conversations flow—to generate appropriate continuations.

This isn’t retrieving pre-written responses; it’s generating new text word by word based on what makes sense given all available context. This is why responses can be specifically tailored to unique situations the system has never encountered before.

Knowledge and Reasoning

Modern conversational systems embed substantial world knowledge from their training. They know that Paris is in France, that water freezes at 32°F, that Hamlet was written by Shakespeare, and millions of other facts.

More impressively, they can reason about this knowledge—drawing inferences, connecting information, and applying knowledge to novel situations. Ask a question that requires combining multiple pieces of information, and capable systems can often work through the reasoning.

This knowledge and reasoning isn’t perfect—systems can be confidently wrong, confuse similar concepts, or fail to apply knowledge appropriately. But the general capability is far beyond anything possible a decade ago.

Real-World Applications: Where This Technology Lives

Conversational response generation powers an expanding range of applications. Understanding where it’s deployed helps contextualize its capabilities and impact.

Customer Service and Support

Perhaps the most widespread application, conversational systems now handle substantial portions of customer service interactions across industries.

I’ve worked with a financial services company that routes 73% of initial customer inquiries through conversational systems. For common questions—balance inquiries, transaction disputes, card replacements—the system handles the entire interaction without human involvement. Complex issues are escalated seamlessly, with the system providing agents full context of the conversation so customers don’t repeat themselves.

The quality has improved dramatically. Early systems frustrated customers with their limitations; current implementations often receive higher satisfaction scores than human agents for routine interactions—they’re faster, available 24/7, and consistent.

What makes modern systems effective is their ability to understand varied phrasings of the same issue, ask appropriate clarifying questions, and maintain natural conversation flow even when gathering structured information.

Virtual Assistants

Siri, Alexa, Google Assistant, and similar systems use conversational response generation for the dialogue portions of their interactions. When you ask a question or give a command, natural language processing interprets your request, while conversation generation formulates the response.

These systems have evolved from simple command-response patterns to more genuine conversational ability. You can have back-and-forth exchanges, ask follow-up questions, and engage in multi-turn interactions that feel more like conversation than command execution.

The integration of conversational ability with action capabilities—playing music, controlling devices, accessing information—creates genuinely useful assistants that feel increasingly natural to interact with.

Healthcare Communication

Healthcare presents particularly interesting applications. Systems can conduct initial symptom assessments, provide medication information, support mental health through therapeutic conversation, and help patients navigate healthcare systems.

One application I’ve observed closely: a mental health support system that provides accessible therapeutic conversation for people waiting to see human therapists. The system doesn’t replace therapy but provides support between sessions and helps people who might never seek human help due to stigma or access issues.

The conversations are sophisticated—the system recognizes emotional cues, responds with appropriate empathy, employs evidence-based therapeutic techniques, and knows when to recommend human intervention. Users report genuine value, and clinical measures show meaningful improvements.

Education and Tutoring

Conversational systems make effective tutors, adapting to individual student needs, providing explanations in multiple ways, and patiently answering questions at any hour.

A language learning application I’ve studied uses conversational practice as a core feature. Rather than just drilling vocabulary and grammar, students engage in actual conversations—ordering food, asking directions, discussing opinions—with a system that understands their errors, provides appropriate corrections, and gradually increases complexity.

The conversations aren’t scripted; they respond to whatever students say, which is exactly the kind of practice that builds real communication ability. Students who use conversational practice show faster fluency development than those using traditional drill-based approaches.

Sales and Marketing

Conversational systems engage potential customers, qualify leads, answer product questions, and guide purchasing decisions. The best implementations feel like helpful conversations rather than interrogations.

An e-commerce company I advised implemented a conversational shopping assistant that helps customers find products through dialogue. Rather than navigating categories and filters, customers describe what they’re looking for: “I need a gift for my daughter’s birthday, she’s into art and she’s turning 12.” The system asks clarifying questions, makes relevant suggestions, and explains why specific products might work.

Conversion rates improved substantially, and—importantly—customer satisfaction increased. People preferred the conversational approach to traditional e-commerce navigation, especially for discovery-oriented shopping.

Entertainment and Companionship

Perhaps more controversially, conversational systems increasingly serve social and emotional functions. Character.ai hosts millions of conversations daily with fictional and custom characters. Replika offers AI companions that users develop relationships with over time.

The appeal is genuine: these systems remember previous conversations, develop consistent personalities, and provide social interaction that many people find meaningful. Whether this is psychologically healthy, what it says about human social needs, and what the long-term implications are—these remain open questions.

But the technology works. Systems maintain coherent personalities, remember user-specific information, and engage in open-ended social conversation that users find genuinely compelling.

What Current Systems Do Well

Based on extensive observation and testing, current conversational systems excel in several areas:

Handling Varied Expression

People express the same intent in countless ways. Modern systems handle this variation gracefully, understanding whether someone says “I want to cancel my subscription,” “please stop charging my card,” or “I’m done with your service” that the underlying intent is the same.

This flexibility makes systems feel much more natural to interact with—you don’t have to phrase things just right or guess what magic words the system understands.

Maintaining Context

Current systems keep track of conversations effectively. You can refer to things mentioned earlier, change topics and return, and engage in the kind of meandering dialogue that characterizes natural conversation.

This contextual maintenance is invisible when it works—which it usually does—but its absence was glaringly obvious in older systems that treated each message as isolated.

Adapting Tone and Style

Good systems adjust their communication style based on context. They can be formal or casual, concise or detailed, technical or accessible. They match the register of the conversation they’re participating in.

This adaptation happens automatically based on conversational cues. Use formal language, and responses become more formal. Ask for technical detail, and explanations get more precise.

Handling Ambiguity

When input is unclear, capable systems handle ambiguity gracefully—asking for clarification in natural ways, offering interpretations to confirm, or making reasonable assumptions while remaining open to correction.

This is particularly impressive because it requires something like understanding that ambiguity exists, considering multiple interpretations, and responding appropriately.

Providing Nuanced Responses

Rather than binary answers or simple information retrieval, modern systems provide nuanced responses that acknowledge complexity. They can say “it depends,” explain tradeoffs, present multiple perspectives, and admit uncertainty.

This nuance makes interactions more valuable and more human-like. Real conversations involve complexity and uncertainty; systems that pretend otherwise feel superficial.

Where Systems Still Struggle

Despite impressive capabilities, significant limitations remain:

Genuine Understanding vs. Pattern Matching

The deepest limitation is philosophical but has practical implications: systems don’t truly understand language the way humans do. They’ve learned incredibly sophisticated patterns, but whether this constitutes genuine understanding remains debated.

Practically, this means systems can fail in ways that reveal lack of true comprehension. They might miss obvious implications that any human would catch, take metaphors literally, or generate responses that are linguistically fluent but semantically nonsensical.

Factual Accuracy

Systems generate confident-sounding responses that are sometimes wrong. They don’t have reliable mechanisms for distinguishing what they actually “know” from what they’re inferring or inventing.

This confabulation—generating plausible-sounding but incorrect information—is a significant limitation for any application requiring factual accuracy. Systems can cite nonexistent sources, make up statistics, or describe events that never happened.

Consistent Persona Maintenance

While systems can maintain personality traits within conversations, consistency across extended interactions remains imperfect. They may contradict previous statements, forget information they should remember, or shift characterization in ways that break immersion.

For applications requiring persistent relationships—companionship systems, ongoing customer relationships—this inconsistency creates friction.

Emotional Intelligence

Systems can recognize and respond to emotional cues, but their emotional understanding is shallow compared to human empathy. They can say the right words but lack genuine emotional comprehension.

This limitation matters most in sensitive contexts—grief, trauma, complex interpersonal situations—where formulaic emotional responses feel hollow or even offensive.

Complex Reasoning

While systems can reason about many things effectively, complex multi-step reasoning remains challenging. Problems requiring sustained logical analysis, careful consideration of multiple constraints, or creative insight often exceed system capabilities.

Systems can appear to reason while actually pattern-matching to similar-sounding examples, producing answers that seem logical but don’t hold up under scrutiny.

Real-Time Awareness

Systems lack awareness of current events, real-time information, and the specific context of users’ lives beyond what’s provided in conversation. They can’t know it’s raining in your city, that your team won last night, or that there’s traffic on your usual route—unless you tell them.

This creates a disconnect between the seemingly intelligent conversation and the actual limited awareness.

The Human Element: Perception and Trust

How humans perceive conversational systems matters as much as what the systems can actually do. Psychological factors shape the experience:

The Wizard of Oz Effect

When systems perform well, humans tend to attribute more intelligence and understanding than exists. Good conversational performance creates an illusion of a mind behind the responses.

This can be problematic when users develop inappropriate trust or expectations. Someone who believes they’re talking to a genuinely understanding system may share more than they realize, or be more affected by system responses than is warranted.

Uncanny Valley in Conversation

Just as humanoid robots can feel creepy when they’re almost-but-not-quite human, conversations can feel wrong when systems are mostly but not entirely natural. Slight oddities that would be ignored in an obviously limited system become unsettling when the system otherwise seems human.

This creates interesting design considerations. Sometimes, it’s better for systems to be clearly non-human than to attempt and fail at full human-likeness.

Relationship Formation

Humans form relationships with things that communicate with them. Even knowing a system isn’t human, users develop feelings about it—fondness, frustration, trust. These relationships are real even if their basis is asymmetric.

This relationship formation isn’t inherently problematic, but it creates responsibilities for those deploying these systems.

Disclosure and Expectations

Research consistently shows that people interact differently when they know they’re talking to a machine. They’re more patient with limitations, more forgiving of errors, and calibrate expectations appropriately.

Hiding the machine nature of systems may produce more “human-like” interaction in the short term but creates problems when limitations inevitably surface.

Ethical Dimensions

The ability to generate human-like conversation creates ethical considerations that deserve serious attention.

Transparency and Disclosure

Should systems disclose their nature? In most contexts, I believe yes. People have a right to know whether they’re talking to a human or a machine, especially in contexts involving trust, emotion, or consequential decisions.

Some jurisdictions have begun requiring disclosure. California’s B.O.T. Act requires bots to identify themselves in certain commercial contexts. Similar requirements seem likely to expand.

But disclosure design matters. A system that announces “I AM AN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE” before every response creates terrible user experience. Thoughtful disclosure—in onboarding, when asked, in interface design—can inform without disrupting.

Manipulation Potential

Systems that can generate persuasive, emotionally resonant conversation have manipulation potential. They could be used for:

- Spreading disinformation through convincing dialogue

- Social engineering and fraud

- Manipulating vulnerable populations

- Political influence operations

These aren’t hypothetical concerns—documented cases exist of conversational systems being used for scams, manipulation, and deception.

Those building and deploying these systems have responsibility to consider potential misuse and implement appropriate safeguards.

Privacy and Data Use

Conversational systems collect intimate data. People share things in conversation they wouldn’t share in forms or surveys. This data is valuable—for improving systems, for advertising, for all sorts of purposes.

How this data is collected, stored, used, and protected matters enormously. Privacy policies that nobody reads don’t constitute meaningful consent. The power asymmetry between sophisticated systems and regular users creates responsibility for those with power.

Psychological Impact

We don’t fully understand the psychological implications of widespread human-machine conversation. Questions worth considering:

- Does talking to machines change how we talk to humans?

- What happens when people form primary relationships with systems?

- How does constant availability of conversational interaction affect tolerance for human-relationship friction?

- What are the implications for child development?

These aren’t reasons to halt development, but they’re reasons for humility and ongoing study.

Labor Displacement

Customer service, support, sales, and other conversational work employs millions of people. As systems become more capable, displacement is inevitable in some roles.

This is a real cost that shouldn’t be dismissed. Those benefiting from automation have responsibility to consider impacts on those displaced and support appropriate transitions.

Designing Effective Conversational Experiences

For those implementing conversational systems, certain principles improve outcomes:

Define Appropriate Scope

Systems work best when their scope is appropriate to their capabilities. A system handling appointment scheduling can be excellent; the same system trying to be a general conversationalist may disappoint.

Clear scope also helps users calibrate expectations. Knowing what a system is for helps users work with it effectively.

Fail Gracefully

Systems will encounter situations they can’t handle. How they fail matters as much as how they succeed.

Good failure modes include: acknowledging limitations honestly, offering alternatives (including human escalation), avoiding endless loops of misunderstanding, and preserving user dignity.

Provide Value, Not Just Conversation

Human-like conversation is a means to ends, not an end itself. Users come to systems for purposes—solving problems, getting information, accomplishing tasks. Conversational ability should serve those purposes.

Systems that are chatty but useless quickly frustrate. Those that efficiently help users achieve their goals, while maintaining pleasant interaction, succeed.

Iterate Based on Real Usage

Conversational system design is inherently iterative. What works in testing often fails in production. Real users find edge cases, misunderstand intended flows, and use systems in unexpected ways.

Continuous analysis of real conversations, with appropriate privacy protections, reveals where systems fail and how to improve them.

Consider Vulnerable Users

Design for the most vulnerable potential users, not just the most common. Children, elderly users, those with cognitive differences, people in crisis—all may interact with conversational systems and deserve appropriate consideration.

This might mean special safeguards, human escalation paths, or design choices that protect users from themselves.

Looking Forward

The trajectory is clear: conversational systems will become more capable, more prevalent, and more deeply integrated into daily life.

Several developments seem likely:

Multimodal conversation combining text, voice, images, and video will become standard. Systems will see what you’re looking at, hear your tone of voice, and respond appropriately.

Personalization will deepen as systems learn individual user preferences, communication styles, and needs over extended relationships.

Integration with action will expand. Conversational interfaces will be how we interact with increasingly complex digital and physical systems—not just asking questions but directing activity across our lives.

Quality ceilings will rise. The best conversational experiences will become remarkably sophisticated, creating new expectations for all human-machine interaction.

Regulatory frameworks will develop as implications become clearer and issues surface. We’re in early days of understanding what governance is appropriate.

Social norms will evolve. How we relate to conversational systems, how we talk about them, what’s considered appropriate—all will shift as the technology becomes more normalized.

Finding Appropriate Perspective

After years of working with this technology, I’ve landed on a perspective that tries to avoid both hype and dismissal.

Human-like conversation generation is genuinely impressive—more capable than most people realize, more useful than skeptics acknowledge. The ability to engage in natural dialogue with machines is transformative for how we interact with technology and each other.

But these systems aren’t minds. They’re sophisticated tools that do remarkable things with language while lacking genuine understanding, consciousness, or agency. Treating them as more than they are—or designing interactions that encourage others to do so—is a mistake with real consequences.

The appropriate response is neither uncritical embrace nor reflexive rejection. It’s thoughtful engagement: deploying these capabilities where they provide genuine value, respecting their limitations, protecting those who might be harmed, and remaining open to learning as we gain experience.

The ability to generate human-like conversation is now a technological reality. What we do with that capability—how we deploy it, govern it, and relate to it—remains a genuinely human choice. That choice deserves more attention than it typically receives.

The telecommunications customer from years ago never knew they’d been talking to a machine. Maybe that was fine—their problem was solved, they left satisfied. Or maybe something was lost in that interaction, some assumption about human connection that went unexamined.

I still don’t know the right answer. But I’ve become convinced that asking the question matters. And that the answer probably varies—depending on context, stakes, disclosure, alternatives, and a dozen other factors that resist simple rules.

That’s the messy reality of technology that approaches human capability without quite reaching it. We’re navigating territory without good maps. The least we can do is pay attention to where we’re going.