The first time I watched one of our warehouse robots make a split-second decision that prevented a collision with a human worker, I gained a new appreciation for what real-time AI actually means in practice. The robot had been navigating a busy fulfillment center aisle when an employee stepped unexpectedly from behind a shelving unit. In approximately 180 milliseconds—faster than the human blink reflex—the robot had processed visual data, predicted the person’s trajectory, calculated multiple avoidance options, selected the optimal path, and initiated a controlled stop while signaling its intent.

That moment captured something I’d been working toward for years: machines that don’t just react to their environment, but genuinely understand and anticipate it at speeds no human operator could match.

Real-time decision making represents one of the most demanding challenges in robotics. Unlike offline AI systems that can take their time processing data and generating responses, robotic systems operating in dynamic environments must perceive, decide, and act within milliseconds—often with incomplete information, uncertain conditions, and zero margin for error. Getting this right has consumed my career, and I want to share what I’ve learned about where this technology stands today and where it’s heading.

The Real-Time Imperative: Why Speed Changes Everything

Traditional AI development often focuses on accuracy: given enough time and data, produce the best possible answer. Robotic real-time systems flip this priority. A perfect decision that arrives too late is worthless. A good decision that arrives in time can save lives.

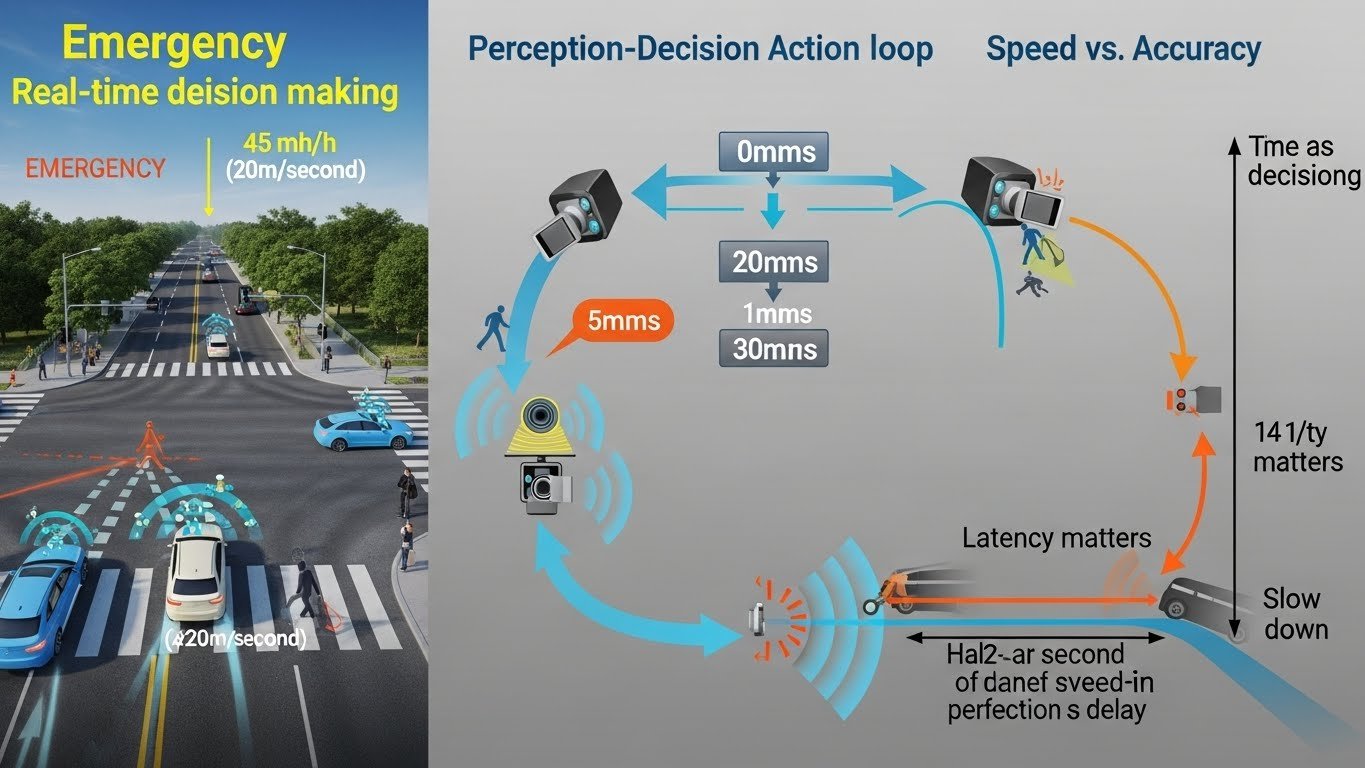

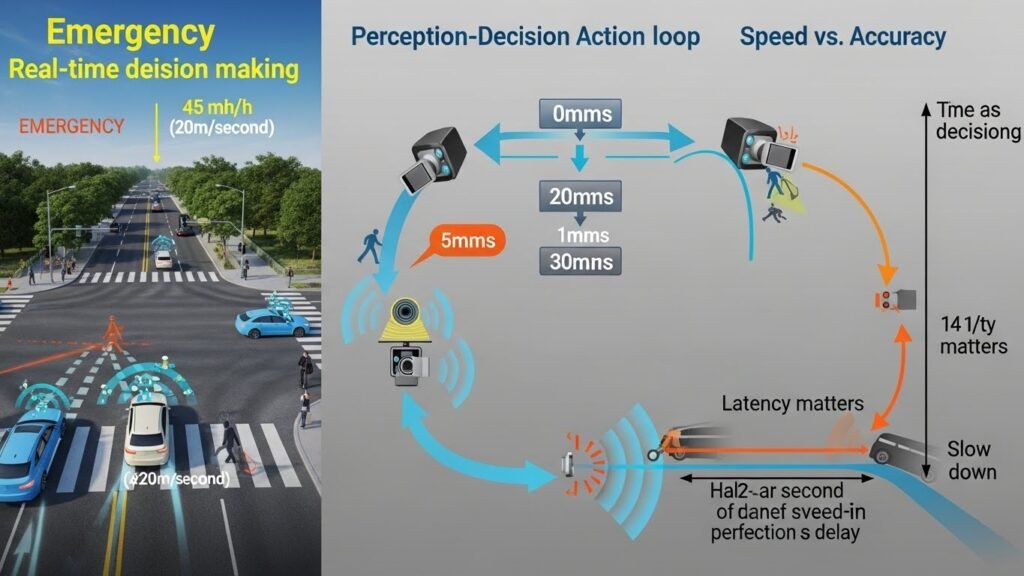

Consider an autonomous vehicle approaching an intersection at 45 miles per hour. The vehicle travels approximately 20 meters per second. If the perception-to-action pipeline takes 500 milliseconds—half a second, which feels instantaneous to humans—the vehicle has traveled 10 meters before any response occurs. In emergency situations, that delay is the difference between a near-miss and a catastrophe.

This temporal constraint fundamentally shapes every aspect of how AI systems for robotics are designed, trained, and deployed. Algorithms that achieve state-of-the-art performance in benchmarks may be completely unusable if they can’t meet latency requirements. Elegant solutions get rejected in favor of faster approximations. Engineering trade-offs that seem counterintuitive from a pure AI perspective become essential when milliseconds matter.

I’ve seen research teams achieve remarkable results in simulation only to discover that their approaches couldn’t run fast enough on actual robot hardware. The gap between academic benchmarks and real-world deployment often comes down to this simple question: can you do it fast enough?

The Perception-Decision-Action Loop

Every robotic decision-making system operates within what engineers call the perception-decision-action loop. Understanding this cycle illuminates where AI makes its contributions and where the hardest challenges lie.

Perception: Making Sense of the World

Robots perceive their environment through sensors: cameras, LiDAR, radar, ultrasonic sensors, inertial measurement units, force-torque sensors, and increasingly sophisticated tactile arrays. Raw sensor data is meaningless until processed into useful representations—recognizing that a particular cluster of pixels represents a human, that a pattern of LiDAR returns indicates an approaching vehicle, that a force signature suggests the robot is gripping its target correctly.

Modern perception systems leverage deep neural networks extensively. Convolutional networks process visual data to detect objects, segment scenes, and estimate depths. Point cloud networks interpret LiDAR data. Multi-modal fusion systems combine information from different sensor types to build robust environmental understanding.

The challenge is doing this fast enough. A typical autonomous vehicle might generate over a gigabyte of sensor data per second. Processing this torrent in real-time requires both algorithmic efficiency and specialized hardware. I’ve spent countless hours optimizing neural network architectures not for accuracy improvements of a few percentage points, but for inference speed improvements of a few milliseconds.

Decision: Choosing What to Do

Once the robot understands its environment, it must decide how to act. This is where AI for robotics gets philosophically interesting, because “deciding” encompasses a remarkable range of cognitive tasks.

At the simplest level, decision-making might involve selecting from predefined behaviors based on current conditions. A warehouse robot detects an obstacle and chooses to stop, detour left, or detour right based on available clearance. This can be handled through classical planning algorithms or decision trees.

At more complex levels, robots must generate novel solutions to unprecedented situations. A surgical robot encounters unexpected tissue characteristics and must adapt its approach in real-time. A disaster response robot navigates debris fields that no training data exactly anticipated. These situations require AI systems capable of generalization—applying learned principles to new circumstances.

Reinforcement learning has proven particularly valuable for developing decision-making policies that can handle continuous action spaces and complex, sequential choices. Robots trained through simulation can develop sophisticated behaviors that transfer to real-world performance, though getting this sim-to-real transfer to work reliably remains an active area of development.

Action: Executing in the Physical World

Decisions must translate into physical movements. Motors must turn. Grippers must engage. Vehicles must accelerate or brake. This final stage introduces its own latencies and uncertainties.

Physical systems have dynamics—they can’t change direction instantaneously or accelerate without limits. Effective real-time AI must understand these constraints and make decisions compatible with what the robot can physically execute. There’s no point deciding to stop immediately if the robot’s maximum deceleration means it will travel another meter regardless.

Control systems that translate high-level decisions into low-level motor commands operate at the fastest time scales in the robot architecture—often 1,000 Hz or faster. AI increasingly contributes at this level too, with learned controllers adapting to variations in robot mechanics, wear patterns, and environmental conditions.

Core AI Technologies Driving Progress

Several AI approaches have proven particularly valuable for real-time robotic decision-making. Each offers different strengths and suits different aspects of the challenge.

Deep Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning trains agents to make sequential decisions that maximize cumulative rewards over time. For robotics, this approach can develop sophisticated control policies directly from experience—learning, for example, how to make a bipedal robot walk by trial and error rather than explicit programming of every movement.

The breakthrough came with deep reinforcement learning, combining neural networks with RL algorithms to handle high-dimensional sensory inputs and complex action spaces. Robots trained this way have learned to manipulate objects with human-like dexterity, navigate complex environments, and perform athletic maneuvers that would be nearly impossible to program explicitly.

I worked on a project where we trained robotic arms to perform assembly tasks through reinforcement learning. The conventional approach would have required precise calibration and explicit programming for each movement. Instead, we defined the goal—parts correctly assembled—and let the system discover how to achieve it. The resulting policies were more robust to positioning errors and part variations than our hand-coded alternatives.

The real-time advantage of deep RL comes from policy inference. Once a policy is trained—which can take days or weeks—executing it requires only a forward pass through a neural network. Well-designed policies can run in single-digit milliseconds, enabling responsive real-time control.

Computer Vision and Perception Networks

Modern robotic perception relies heavily on convolutional neural networks and, increasingly, transformer architectures adapted for visual processing. These systems detect objects, segment scenes, estimate poses, and interpret spatial relationships at speeds that enable real-time applications.

The evolution has been remarkable. Early deep learning approaches for object detection were too slow for real-time use, requiring hundreds of milliseconds per frame. Modern architectures like YOLO variants, EfficientDet, and specialized real-time transformers achieve comparable or better accuracy while running at 30+ frames per second on edge hardware.

For robotics, specialized perception networks have emerged that target specific use cases. Pose estimation networks determine the position and orientation of objects for manipulation. Instance segmentation networks identify individual objects even when overlapping. Depth estimation networks infer 3D structure from standard cameras. Each represents AI capability that was effectively impossible a decade ago, now running fast enough for real-time robotic use.

Sensor Fusion and Multi-Modal Learning

Real-world robots rarely rely on a single sensor type. Cameras provide rich visual information but struggle in poor lighting or adverse weather. LiDAR offers precise distance measurements but can’t read signs or recognize faces. Radar penetrates fog and rain but provides lower resolution. Combining these sensor modalities creates more robust perception than any single source could provide.

AI approaches to sensor fusion range from classical probabilistic methods like Kalman filtering to modern neural approaches that learn to integrate multi-modal data end-to-end. The most sophisticated systems develop shared representations that capture complementary information from each sensor type, enabling the robot to maintain situational awareness even when individual sensors are degraded.

An autonomous vehicle project I contributed to used a learned fusion approach that dramatically improved perception in challenging weather conditions. When snow degraded our cameras, the system leaned more heavily on radar and LiDAR. When water spray from other vehicles scattered our LiDAR returns, visual data filled the gaps. The AI had learned not just how to fuse sensor data, but how to handle sensor failure gracefully.

Planning and Motion Generation

While neural networks excel at perception and policy execution, classical AI planning algorithms remain essential for many robotic decision-making tasks. Path planning algorithms like RRT* find collision-free routes through complex environments. Motion planning systems generate trajectories that satisfy kinematic and dynamic constraints. Task planning approaches sequence high-level actions to achieve goals.

The integration of learning-based and planning-based approaches represents a current frontier. Learned systems can provide heuristics that make classical planners faster. Planning algorithms can provide structure that makes learned systems more reliable. Hybrid architectures that combine both paradigms often outperform either approach alone.

For real-time applications, anytime planning algorithms are particularly valuable. These methods produce valid solutions quickly while continuing to improve them if additional computation time is available. When a robot must act immediately, it takes the best current plan; when it can wait, it gets something better.

Applications Across Industries

Real-time AI decision-making enables robotic applications that weren’t feasible with traditional programming approaches. The technology is now mature enough for serious commercial and industrial deployment across multiple sectors.

Autonomous Vehicles

Self-driving cars represent perhaps the highest-stakes application of real-time robotic AI. The vehicles must perceive complex, dynamic traffic environments; predict the behavior of other road users; plan safe trajectories; and execute smooth, comfortable maneuvers—all within the tight latency constraints of highway speeds.

The autonomous vehicle industry has driven enormous investment in the underlying technologies. Perception systems now routinely identify and track hundreds of objects simultaneously while running at tens of frames per second. Prediction systems model the probable future behavior of other vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists. Planning systems generate trajectories that optimize for safety, progress, and passenger comfort.

I’ve observed the maturation of this technology over years. Early systems were brittle, handling only carefully geofenced areas under ideal conditions. Current systems navigate complex urban environments with increasing reliability, though the final push to full autonomy in all conditions remains challenging.

Industrial Manufacturing

Factory robots have used AI for decades, but real-time decision-making enables new capabilities beyond traditional automated manufacturing. Rather than following fixed programs with every movement predetermined, modern industrial robots adapt to what they observe.

Vision-guided manipulation allows robots to pick parts from unstructured bins rather than precisely positioned fixtures. Real-time quality inspection identifies defects as products pass through production lines. Collaborative robots work alongside humans, continuously monitoring their environment and adjusting their behavior to ensure safety.

A manufacturing client I worked with implemented adaptive assembly using real-time AI. Their previous system required precise part placement and failed when components varied slightly from specification. The new system visually assessed each part’s actual position and condition, adapting its approach accordingly. Defect rates dropped significantly, and the line could handle component variations that previously would have required manual intervention.

Warehouse and Logistics Robots

The explosion of e-commerce has created enormous demand for warehouse automation. Robots that can navigate dynamic environments, identify and grasp diverse products, and coordinate with human workers offer compelling efficiency gains.

Mobile robots now navigate warehouse floors using real-time perception and planning, avoiding obstacles and finding efficient routes to destinations. Picking systems identify products among thousands of SKUs and determine optimal grasp strategies in real-time. Sorting systems route packages at high speeds based on instantaneous visual recognition.

These environments present particular challenges because they’re semi-structured: more predictable than outdoor environments but far less controlled than traditional manufacturing cells. Humans walk through robot work areas. Products come in endless variety. Layouts change as operations evolve. Real-time AI enables robots to handle this variability without constant reprogramming.

Surgical Robotics

Medical robots operate under perhaps the most stringent requirements for real-time AI. Decisions affecting patient safety must be made quickly, correctly, and transparently. The tolerance for error approaches zero.

Current surgical robots primarily assist human surgeons rather than operating autonomously, but AI increasingly contributes to real-time decision support. Tissue recognition systems identify anatomical structures. Tremor filtering removes unwanted hand movements from surgical manipulations. Force feedback systems prevent excessive pressure on delicate tissues.

Emerging applications push toward greater autonomy: robots that can perform standardized surgical steps under supervision, adjust their approach based on what they observe, and provide predictive guidance to human surgeons. The AI must operate in real-time while meeting rigorous safety and reliability standards.

Aerial Robotics and Drones

Unmanned aerial vehicles face unique real-time challenges related to their flight dynamics. Hovering multirotor drones must make continuous control adjustments at high frequency to maintain stable flight. Fast-moving fixed-wing drones have limited time to react to obstacles or changing conditions.

AI enables aerial robots to navigate complex environments, avoid obstacles, track moving targets, and perform coordinated behaviors with multiple vehicles. Racing drones now use learned controllers that outperform expert human pilots in reaction time and trajectory optimization. Inspection drones autonomously navigate infrastructure, identifying defects and coverage gaps in real-time.

The computational constraints of aerial platforms make real-time AI particularly challenging. Every gram of processing hardware is payload that could otherwise be sensors, batteries, or cargo. Efficient algorithms and specialized edge processors are essential.

Confronting the Hard Problems

Real-time AI for robotics faces challenges that don’t exist—or matter less—in other AI domains. Understanding these difficulties explains why some applications have advanced rapidly while others remain elusive.

Latency Management

Every component of the perception-decision-action pipeline adds latency. Sensors have sampling rates and processing delays. Neural networks require inference time. Communication links introduce transmission delays. Motors have response times. The cumulative latency determines how quickly the robot can respond to environmental changes.

Managing this latency budget requires careful engineering across the entire system. Algorithm designers must know their time allowances and stay within them. System architects must identify and eliminate unnecessary delays. Hardware engineers must select components that meet timing requirements.

I’ve seen projects fail because teams optimized individual components without considering end-to-end latency. A brilliant perception system is worthless if it leaves no time for planning and execution. Real-time robotics requires systems thinking, not just algorithmic innovation.

Handling Uncertainty

Robots operate in the real world, where nothing is known perfectly. Sensor measurements are noisy. Object recognition systems occasionally misclassify. Predictions about future events are inherently uncertain. Physical models don’t perfectly capture reality.

Real-time AI systems must make good decisions despite this uncertainty—ideally, decisions that are robust to the range of possible true conditions rather than optimized for any single assumption. This requires uncertainty quantification: not just deciding what’s most likely, but understanding the spread of possibilities.

Probabilistic approaches help, but they introduce computational costs that can conflict with real-time requirements. The challenge is maintaining sufficient uncertainty awareness while meeting latency constraints.

Safety and Reliability

Robots can injure people and damage property. AI systems can fail in unexpected ways, particularly when encountering situations outside their training distribution. The combination is concerning.

Safety-critical real-time systems require extensive testing, validation, and often formal verification of key properties. But testing AI systems is harder than testing traditional software because behavior emerges from learned models rather than explicit code. You can’t simply trace through the logic to verify correctness.

The industry is developing approaches to AI safety verification, but they remain less mature than traditional safety engineering. Redundancy, monitoring, and graceful degradation provide some protection. Human oversight remains essential for high-stakes applications. But we don’t yet have fully satisfactory answers for ensuring the reliability of AI systems in safety-critical real-time applications.

Generalization and Distribution Shift

AI systems trained on one data distribution may perform poorly when deployed in conditions that differ from their training environment. This is particularly problematic for real-time robotics, where systems may encounter situations they’ve never seen before.

A robot trained in one warehouse may struggle when deployed to another with different layouts, lighting, or products. An autonomous vehicle trained in Arizona may face challenges in Boston’s snow and narrow streets. Sim-to-real transfer from training in simulation to deployment in reality remains imperfect.

Addressing distribution shift requires either extensive training data covering all expected conditions—often impractical—or AI systems capable of genuine generalization from limited examples. Foundation models trained on vast diverse datasets show promise for improved generalization, though adapting them for real-time robotic use remains an active research area.

Hardware Constraints

Real-time AI for robotics must ultimately run on physical hardware deployed on physical robots. This introduces constraints that differ from cloud-based AI development.

Power consumption matters when running on batteries. Size and weight matter when every gram affects robot performance. Heat dissipation matters when processors run continuously without the thermal management available in data centers. Cost matters when deploying hundreds or thousands of robots.

Edge AI processors have improved dramatically—specialized chips that deliver neural network performance within mobile power budgets. But algorithm efficiency remains essential. Models must be designed, trained, and often compressed to meet edge deployment requirements while maintaining real-time performance.

The Hardware Ecosystem

Real-time AI for robotics depends on specialized hardware that’s evolved rapidly in recent years. Understanding this ecosystem helps explain what’s currently possible and where limitations remain.

Edge AI Processors

Dedicated AI accelerators designed for edge deployment have transformed what’s achievable in real-time robotics. NVIDIA’s Jetson platform, Google’s Edge TPU, Intel’s Movidius, and similar offerings from other vendors provide neural network inference at speeds and power levels suitable for robotic platforms.

These processors differ from cloud GPUs in fundamental ways. They sacrifice peak performance for power efficiency. They often optimize for inference rather than training. They support specific model architectures particularly well while others may run slowly or not at all.

I’ve learned that hardware selection significantly affects algorithm design. Knowing your target platform from the beginning lets you design models that run efficiently rather than discovering deployment problems late in development.

Sensor Technologies

Real-time perception is only as good as the sensors providing data. Advances in sensor technology directly enable improved AI decision-making.

LiDAR has become cheaper and more capable, with solid-state systems offering improved reliability over mechanical scanning. Camera sensors have improved in low-light performance and dynamic range. Radar systems have achieved higher resolution. Time-of-flight cameras provide depth information at high frame rates.

Equally important are sensor interfaces and synchronization. Real-time systems need precisely timed sensor data with minimal latency. Modern sensor architectures expose this timing information and support tight integration with processing systems.

Communication Infrastructure

When real-time AI processing is distributed—some on the robot, some at the edge, some in the cloud—communication latency becomes part of the timing budget. 5G networks promise low-latency wireless communication that could enable new architectures, but practical deployments still face reliability and coverage challenges.

For most current real-time applications, the safest approach keeps critical decision-making on the robot itself, avoiding dependency on network connections that could fail or lag at crucial moments. Cloud resources can provide higher-level intelligence—planning, learning updates, fleet coordination—while real-time responses happen locally.

Ethics and Responsibility

Real-time AI decision-making in robotics raises ethical questions that deserve serious consideration. These systems make consequential decisions—sometimes life-or-death decisions—without human involvement.

Accountability and Transparency

When a robot makes a harmful decision, who is responsible? The robot’s manufacturer? The AI developer? The operator? The owner? Traditional liability frameworks developed for human decision-makers don’t translate cleanly to autonomous systems.

The real-time nature of robotic decisions compounds this difficulty. Decisions made in milliseconds may be nearly impossible to audit after the fact. What exactly did the system perceive, predict, and consider when making its choice? Explainable AI approaches help, but interpretability and real-time performance often conflict.

I believe the industry must develop better frameworks for accountability before autonomous systems become more widespread. Waiting for serious harm to force regulatory responses is not responsible development.

Algorithmic Bias

AI systems can perpetuate or amplify biases present in their training data. For real-time robotics, this might manifest as perception systems that perform poorly for certain demographics, or decision-making policies that impose unequal risks on different groups.

Testing for such biases is essential but challenging. Real-time systems must be evaluated not just for average-case performance but for failure modes across all populations that might encounter them. An autonomous vehicle that reliably detects some pedestrians but misses others is not acceptable regardless of its overall metrics.

Autonomy and Human Oversight

How much decision-making authority should we grant to real-time AI systems? The technology enables robots to make choices faster than humans can intervene, but faster isn’t always better if the decisions are wrong.

Finding the right balance between autonomy and oversight depends on context. Where the stakes are high and AI reliability is uncertain, human oversight remains essential even if it costs some efficiency. Where AI systems have proven reliable and the consequences of errors are limited, greater autonomy may be appropriate.

I’m cautious about the enthusiasm for full autonomy that sometimes pervades robotics discussions. Humans in the loop aren’t just a fallback for AI limitations—they’re a check on systems that, however sophisticated, remain imperfect.

Looking Ahead

Real-time AI for robotics continues advancing on multiple fronts. Several trends seem likely to shape the field in coming years.

Foundation Models for Robotics

Large pre-trained models—foundation models—have transformed natural language processing and computer vision. Adapting this paradigm for robotics could provide robots with more generalizable capabilities and reduce the need for application-specific training.

Current efforts explore vision-language models that can understand diverse environments through their language grounding. Robotics foundation models trained across many tasks and embodiments show promise for improved generalization. But adapting large models for real-time edge deployment remains challenging.

Sim-to-Real and Synthetic Data

Training real-time AI systems requires data, but collecting real-world robotic data is expensive and potentially risky. Simulation offers an alternative: train in virtual environments, deploy in reality.

The challenge is making simulation realistic enough that learned behaviors transfer effectively. Domain randomization—varying simulation parameters to create robust policies—helps, but significant gaps remain for complex real-world conditions.

Advances in physics simulation, rendering, and procedural content generation continue narrowing this gap. Future systems may train primarily in simulation while requiring only limited real-world fine-tuning.

Continuous Learning and Adaptation

Current real-time AI systems are typically static after deployment: the models are fixed, and the robot applies what it learned during training. Future systems may learn continuously from experience, adapting to changing environments and improving over time.

This introduces challenges around stability—ensuring that continuous learning improves rather than degrades performance—and safety—ensuring that learned adaptations don’t introduce dangerous behaviors. But the potential for robots that improve through experience is compelling.

Human-Robot Collaboration

Rather than replacing humans, many robotic applications involve close collaboration between human and robotic workers. Real-time AI enables this collaboration by giving robots the awareness and responsiveness to work safely alongside humans.

Future systems will likely become more sophisticated in interpreting human intentions, communicating robot plans, and adapting to human preferences and working styles. The goal is not just safe coexistence but genuine partnership that leverages the strengths of both human and robotic intelligence.

Reflections From Practice

After years working in this field, I’ve developed some hard-won perspectives on real-time AI for robotics.

The most important lesson is that real-world deployment is fundamentally different from research success. Lab demonstrations and benchmark performance provide necessary validation, but they don’t guarantee that systems will work reliably in the field. Edge cases, environmental variations, and unexpected interactions expose limitations that controlled testing doesn’t reveal.

I’ve also learned that the AI is only part of the system. Real-time robotic decision-making depends on sensors, actuators, hardware platforms, communication links, and integration engineering as much as on algorithms. Teams that obsess over model architecture while neglecting these fundamentals typically struggle to deploy.

Finally, I’ve come to believe that appropriate humility about AI capabilities is essential, especially for high-stakes applications. These systems are genuinely impressive—I’ve seen them do things that seemed impossible a decade ago. But they’re also genuinely fallible in ways that can be hard to predict or detect. Recognizing both the power and the limitations leads to better, safer systems.

Real-time AI for robotics is no longer an emerging technology—it’s a deployed reality transforming industries from transportation to manufacturing to healthcare. The next decade will bring systems more capable, more generalizable, and more autonomous than anything we’ve seen. Building these systems responsibly, with appropriate attention to safety and ethics, is both an engineering challenge and a moral obligation.

That warehouse robot that stopped for the unexpected worker? It represents a small success in a much larger project: creating machines that can operate safely and effectively in our world. We’re further along that path than many realize, with further still to go.